Art Futures with AI: Practical Encounters in the Creative Sector

Outside certain academic and professional domains, the term “artificial intelligence” (AI) is often used inconsistently and serves as a shorthand for anything involving automation or algorithmic processes. Despite the integration of AI in everyday digital applications, from software updates to email and photography, resistance and apprehension around using it are widespread among many, including artists and creative professionals. These concerns often arise from ongoing challenges in AI development, including algorithmic bias (e.g., gender and racial biases), loss of cultural heritage, and ambiguity around governance and intellectual property – particularly as AI systems appropriate and replicate artistic styles honed over years of artistic practice. These themes are central to the work of Claudia Larcher, a Vienna-based artist, experimental filmmaker and AI researcher, with whom we have discussed the implications of AI-related sociotechnical transformation for the art scene, the art market, and creative practice more broadly. All material presented herein is drawn from a comprehensive interview with the artist in her Viennese studio in April 2025.

Larcher, whose artistic practice is in the field of media art, describes working with AI as both, “quite fun” and “scary”. Her workshops with various audiences focus on demystifying AI, encouraging critical, creative engagement with it and discovering its potential for developing new ways of approaching self-expression and work. By facilitating creative professionals and others in understanding their capacity for agency, the artist shares a way of staying resilient and coping with anxieties about occupational displacement and self-identity. In one of her recent workshops at Wien Museum (the Vienna Museum), Larcher noticed how the idea of engaging with AI can overwhelm many people, regardless of age or background, even though most participants are already interacting with it daily, through phones or software updates. In one of the sessions, which included over 60 attendees, it became clear that concerns are especially pronounced in the arts and creative industries. Artists worry about their professional relevance, asking whether their skills are becoming obsolete, and the unease is even higher among those in applied arts, such as graphic designers, photographers and journalists. Having dedicated years to training and establishing client relationships, many now find themselves in mid-career, often in their forties, facing clients turning away in favour of more affordable or do-it-yourself AI-based solutions. In her workshops, Larcher aims to share her perspective: despite these challenges, there are also opportunities. With a hands-on, experiential approach to workshops, she helps participants to engage with AI actively and directly, discovering its potential to also be “playful and empowering” – the aspects that are particularly pronounced in her own artistic work.

Problematising AI

In 2022, during a workshop for artists in San Francisco, Larcher chose to address gender bias in AI – a concern evident in both, her personal encounters with AI models and in broader critical literature (Crawford, 2021). Kate Crawford’s Atlas of AI (2021) argues how AI perpetuates and amplifies pre-existing hierarchies by classifying and simplifying the world according to problematic historical patterns, while also consolidating power in the hands of those who design and deploy AI systems. She critically analyses large-scale datasets like ImageNet and the sociotechnical, ethical, and political stakes of their use, highlighting how problematic labelling, lack of representation, and non-consensual image use embed bias and ultimately reinforce social inequalities. Similarly, Larcher’s research and artistic inquiry shows how official European historiography systematically erased or omitted women and other marginalised groups not due to their absence, but because such presences were not in line with the political interests or societal narratives.

The perpetuation of these biases in AI demonstrates well how it is not an objective or neutral technology, but is fundamentally material, extractive, and political (Crawford, 2021). This disproportionately affects the representation of women, as AI training largely draws on internet data and problematic content, such as hypersexualised and pornographic images, routinely ignoring those outside stereotypical age or professional categories. Working with AI models to generate images for her projects, Larcher discovered that images of women in roles traditionally associated with men (e.g., politicians wearing suits) are often censored or distorted, reflecting the stereotypical patterns of AI training.

An additional layer of subjective bias is introduced as data labelling is outsourced to workers in the ‘Global South’, where structural inequalities, disparities in education and distinct cultural context might shape individuals’ perspectives. Many platforms claim to have reduced bias in AI, but their methods mostly rely on filtering results or adjusting prompts in ways that hide the underlying problems. In some cases, a user’s request is altered into a different input without the user knowing, raising questions about transparency and user control. At the same time, recent political shifts especially in the United States have rolled back diversity and inclusion initiatives. This has made it easier for openly biased models to be released without even the appearance of neutrality. The risk is especially concerning given that many AI systems work as “black boxes”: their decision-making is obscured and spotting in-built bias becomes difficult. Unlike human bias, which is often geographically or culturally constrained, AI bias can spread quickly, affecting diverse populations simultaneously without clear points of intervention. There remains hope, however, that properly designed AI systems can address some of these issues.

Rethinking AI

In her work, Claudia Larcher goes beyond problematising AI development and highlights the ways of employing AI technologies to ‘rewrite’ the past by closing potential gaps (Larcher, 2022-2024), thus claiming agency to different futures with and through AI. She also notes the importance of regulation – such as the EU’s efforts in developing frameworks that address copyright violations – for ethical AI and artists rights protection, particularly the work of illustrators, whose styles get appropriated. Some AI systems already avoid generating images of living public figures to respect personal rights – although such practices require constant review and enforcement.

For Larcher, keeping up with developments in AI necessitates a research activity two weeks before her workshops, for which she has also developed some guidelines. She suggests drawing on Caroline Sinders’ (2020) Feminist Data Set handbook, which offers critical guidance on data selection through a feminist lens, emphasising inclusivity and reflexivity in identifying relevant sources. The artist also recommends using her own curated deep fake dataset, designed deliberately to address representational gaps, but cautions against using AI-generated outputs as a historical source. At the same time, Larcher is aware that the process of “filling gaps” in historical datasets with AI-generated material is inherently subjective. While focusing on human rights principles as the guiding values might help in making decisions about what is appropriate, such interventions can and should extend beyond human centric perspectives. According to the artist, recognising the interconnectedness of humans, plants, animals, and ecosystems is equally important and cannot be reasonably postponed. This perspective aligns with critical posthumanist thought, which argues that addressing justice and sustainability necessitates simultaneous, intersectional action at multiple levels.

In an exhibition project in South Africa – IMAGINE AI FOR DIGNITY - Feminine Visions for Regeneration (March 16-23, 2025) - Larcher with her friend, curator and festival director Eva Fischer sought to counter the current Silicon Valley discourse valorising “masculine energy” by bringing in the attributes that are projected on femininity – such as care, fairness, cyclical growth, cooperation, and regeneration – not as gendered traits per se, but as systemic principles often perceived as weak in business and technology contexts. Inspired by Rutger Bergman’s (2020) “Humankind: A Hopeful History” and their friend’s fondness for referring to the concept of “survival of the friendliest” (likely from an eponymous book by Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods (2020)), Larcher and Fischer offer an alternative approach to understanding human evolution as shaped more by communication than by strength. Rethinking AI through the values of care, healing and sustainability, their perspective, seen also within a framework of critical posthumanism, insists on addressing human, animal, and ecological rights simultaneously, recognising the interdependence of all actors within planetary systems. In such vision, AI could play a constructive role if it is trained to perceive and respond to such entanglements rather than privileging species hierarchies. Given AI’s capacity to process vast datasets at speeds beyond human capability, its societal impact depends critically on the curation of training data – prioritising high-quality, inclusive, and ethically sourced material over indiscriminate harvesting of the abundant, yet often distorted or trivial, digital content currently available. These themes are poetically explored in a song FEMININE BEATS MASCULINE ENERGY (Fischer & Larcher, 2025), which Larcher and Fischer produced for the exhibition.

Reflecting with AI

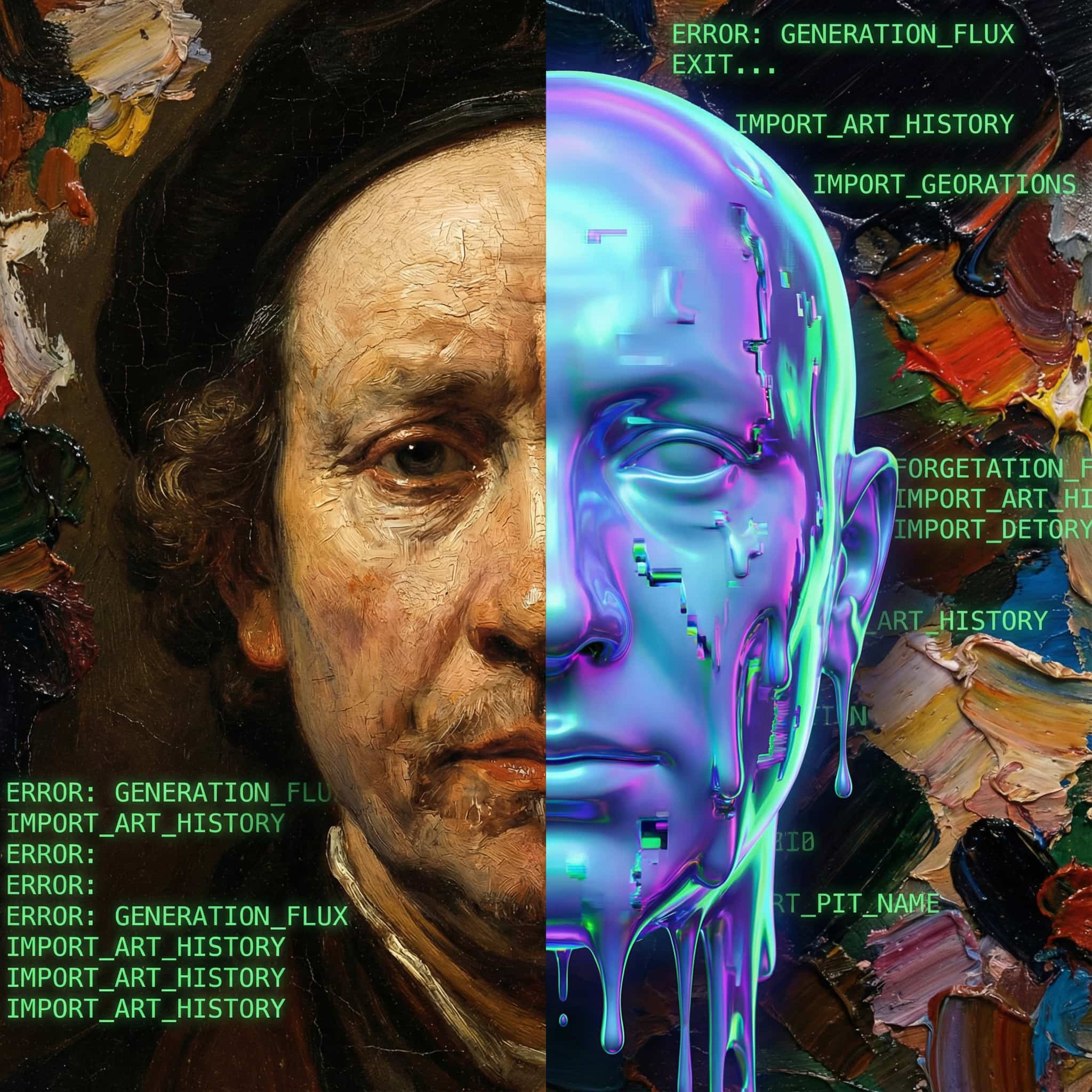

Rethinking AI’s potential for ‘closing the gaps’ is particularly prominent Claudia Larcher’s (2022-2024) AI and the Art of Historical Reinterpretation – Filling gender bias gaps project, where she uses the technology of deep fakes as both, a form of intervention and as a subject of reflection. While ethical AI development still has significant room for advancement, the artist’s strategy is to “set a trap” for these systems’ training by revisiting and augmenting archival histories. Through deep faking images with AI, Larcher is assembling an ever-expanding, fictional ‘historical’ image archive that centres inclusivity and diversity. The resulting dataset serves both as a resource for public engagement and as a training corpus for future AI models, which often use data for training without consent.

“If they steal it, it is not my problem, I guess”, the artist says.

In physical exhibitions Larcher showcases these deep fake images in analog ‘photograph’ formats, thus drawing attention to the artificiality of these images and prompting audiences to question the conspicuous number of female figures on them and inviting people to think whether these women truly existed. For many viewers, especially women, these interventions highlight the persistent exclusion from historical visibility and authority, evident in well-known imagery, such as the male-only balcony scene at the signing of the Austrian State Treaty. This is a problem that incremental progress alone has not resolved, and if AI systems can shape future societal narratives but their training depends on past data, changing – or technically ‘deep-faking’ the data sets indeed holds a transformative potential.

Larcher realises that the datasets in this project are not enough, necessitating efforts to expand them. Initially focusing on art history, she began by engaging with archives at the VALIE EXPORT Center and subsequently expanded her research through engaging with MIT archives and working with institutions such as Ars Electronica. The dataset from the MIT history archive consisted of a hundred images, where women appear in some photos but are often unnamed, whereas men are explicitly identified. This gender bias mirrors trends in art history, where despite their historical significance, women have been systematically marginalised in archival records. For example, Larcher references Rachel Ruysch, a renowned Baroque painter from the Netherlands whose prominence during her lifetime contrasts with her subsequent marginalisation in art-historical narratives; her works, including one housed in the Art History Museum in Vienna, exemplify the broader pattern of overlooked female contributions.

Larcher critiques the early hype around AI-generated images and notes that the practice of deep-faking historical moments is not new. Her approach often involves altering only small details of images rather than entire scenes to evade AI detection systems designed to exclude AI-generated content. This method counters the “Habsburg effect,” where AI systems degrade from repeatedly training on AI-generated outputs, causing homogenisation and diminished quality. Mainstream AI image models, like those from OpenAI, tend to produce outputs with a central perspective and a homogenous style because of extensive repeated use, thus limiting diversity in generated images. In her experiments, Larcher initially worked with older AI models prone to glitches and “hallucinations,” which she found aesthetically and conceptually productive. This experience led her to formulate methodological guidelines that she later applied in her workshops. She emphasizes that working with AI requires a clear concept and well-defined objectives – much like following a recipe that begins with the ingredients already at hand, rather than asking randomly what to cook. A key element of interaction is assigning the model a specific “role” and context, since the algorithm lacks inherent understanding of the user’s expertise level or intentions.

“What is also always important is to tell AI what role it has to take, because AI does not know if I am a child, if I am well educated in physics or not”, the artist suggests.

Adjusting such parameters can encourage less predictable and more creative results. Thus, for Larcher, the successful artistic use of AI relies not on its autonomy, but on deliberate guidance of the process and critical interpretation of its outputs.

At the same time, Larcher stresses the importance of diverse training data, citing DeepSeek as a model valued for its incorporation of diverse datasets. She also notes the linguistic limitations of many US-based AI models, which primarily rely on translated content and lack native inclusivity for languages such as German. In their group show IMAGINE AI FOR DIGNITY - Feminine Visions for Regeneration (March 16-23, 2025) in South Africa, the authors also presented Masakhane, a grassroots initiative focused on collecting and preserving several hundred African languages (out of the thousands spoken on the continent.) Masakhane’s work goes beyond language preservation to include cultural storytelling, gathering data not just about the languages themselves but also about the associated narratives and cultural contexts. The initiative aims to develop and train AI models rooted in these rich, diverse linguistic and cultural datasets, supporting alternative, locally grounded AI systems. Looking ahead, Larcher sees such projects as indicative of the future direction for AI models, particularly for artists. In this context, she refers to Herwig Dunzendorfer’s (ARTECONT gallery) plans to develop an AI platform where artists can upload their work and operate within a closed, decentralised system. This would offer a new model of artistic collaboration and AI use, emphasising data sovereignty and creative autonomy in a secure environment.

Together, these initiatives reflect a shift towards more locally informed, diverse, and artist-centred AI ecosystems that challenge dominant, globalised models by fostering inclusion, cultural specificity, and decentralised control. These nuanced perspectives reflect Claudia Larcher’s critical engagement with sociotechnical dimensions of AI as a researcher and as an artist. Her work is an earnest call for more thoughtful methodologies in AI art practice, she understands and shares the anxieties around AI when it comes to creative work.

Art Futures and AI

In her work, Larcher primarily trains AI models using her own extensive archive of images, accumulated over more than two decades of artistic practice, including numerous film stills. By feeding the system with stills from her films, she enables the AI to imitate her distinct style, resulting in more precise outputs aligned with her artistic vision. This approach also offers practical efficiency, as it reduces the need for site visits; instead, architectural simulations are incorporated into her stylistic guidelines, forming the basis for further work. Typically, she employs multiple AI models in her projects, which interact and influence one another. For instance, she begins with training Midjourney to generate images in her style. These images then serve as input for video AI tools, whose outputs contribute to sound production, creating a multimedia feedback loop. This iterative workflow involves continuous decision-making, similar to traditional artistic process in a studio. Rather than using simplistic prompts, she strategically uses a variety of AI tools (the very ones criticized for displacing creative professionals, she notes) to critically engage with themes of automation and labour displacement. Her methodology reflects a reflexive artistic approach: by confronting prevalent concerns and personal anxieties about AI’s impact, she integrates humour and critical reflection into her work. This enables her to explore and demystify the complex relationship between AI technologies, artistic creation, and socio-cultural issues, positioning her practice at the intersection of technology critique and creative innovation.

According to the artist, acceptance of the digital art, a domain historically marginalised in comparison to classical forms, such as painting, is lagging in both, the art scene and the art market. She notes that collectors continue to privilege materially stable, transportable formats such as oil on canvas, whose physicality aligns with storage, financial speculation, and assetization logics. Paradoxically, amid ongoing technological innovation, some younger artists also valorise analog media over the digital – a trend she regards as unproductive given the extensive historical saturation of analog forms. Although she herself transitioned to digital methods relatively late, an attachment to material production remains; however, her physical works are consistently conceived in relation to, and entangled with, the digital realm. Even though her work ultimately manifests in physical or visible forms that function independently of electronic devices, the artist acknowledges the peculiar nature of digital art production such as working on a computer to create something that can be saved to a USB stick. This tension between digital creation and physical manifestation remains central to her practice.

Although she has developed a recognisable style, particularly in her films, and her works are identifiable when shown, Larcher shares a fear common among fellow artists and friends who are animators that their work might lose its significance in the future because similar results could be produced by AI in seconds. They plan to hold a workshop to address these concerns. At the same time, training AI on her own animation technique could potentially save her two months of work, yet this leads to broader questions: if artistic production becomes so easy, how much art will be created, and what kinds of regulations might the art world need? Such issues are now constant topics of discussion in creative fields. Initially, film festivals refused AI-generated works, but such pieces are now accepted. Just last year, she faced backlash when a competition entry contained a small AI-generated element, with some questioning its eligibility. Today, however, AI tools are embedded in mainstream software such as Adobe Premiere, raising the question of where to draw the line, since almost everyone now uses some AI-generated material, even without realising it. More recently, following an invitation to participate in a radio program alongside several other artists and researchers, discussing AI, art, and copyright, Larcher was told that the moderator could not find any guests who were completely opposed to AI in art – something the artist interprets as a positive sign.

Despite growing recognition of AI’s potential to transform artistic practice, there remains considerable hesitation within the art scene, as evidenced by the slow adoption of such technologies in exhibitions and fairs. This reflects a broader pattern of gradual, uneven acceptance of AI’s role in contemporary art. She encountered resistance when proposing an AI workshop during her university teaching years, with senior colleagues dismissing its relevance. Her own perspective shifted dramatically upon witnessing the capabilities of DALL-E mini's first image generation. While she was familiar with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) that transform input images into image outputs, the radical shift occurred when text prompts alone could generate images. This moment prompted urgent questions about the trajectory of these technologies and their implications for art education. She argues that art universities must immediately engage with these developments, despite institutional reluctance to address such emerging technologies in their curricula. She interprets the reluctance toward engaging with AI in art education as stemming from the necessity of deeply immersing oneself in the medium to grasp its workings. She recalls a student who presented an AI-based work that was scarcely discussed during the critique session, largely because faculty members did not understand what they were seeing. The discussion ended with the dismissive remark that, since the work was made with AI, it required “no effort” – a judgment she found particularly troubling in the context of an art school, because such environments should serve as spaces for critical engagement with emerging media. Years later, she observes that most AI-driven works appear to be produced independently by students using their personal accounts, with only a small number of faculty truly engaged with available AI tools.

While she sees growing awareness that AI may significantly change artistic practice, she also senses a tendency within the art scene to avoid the subject for years to come. This became apparent at a recent art fair in Paris, where she noted the near-total dominance of painting among contemporary works, underscoring the slow pace at which technological shifts permeate the art market and exhibition culture. At the same time, Larcher observes that AI is becoming a theme in contemporary exhibitions, although she distinguishes her practice by emphasising that her work carries deeper layers of meaning beyond the mere use of AI technology. One of her current projects addresses the end of cinema and engages critically with issues of AI ethics and the anxieties surrounding AI’s potential to dominate creative markets. Despite her expertise, Larcher remains uncertain about the future trajectory of AI’s role in art and society given its complexity.

The artist is aware of AI’s environmental costs and argues that systemic regulation of large tech corporations is essential, advocating for EU to focus on smaller, decentralised models that can run locally and be tailored to specific tasks. She sees the release of alternatives like China’s DeepSeek as valuable for opening debate on efficient, small-scale AI training, stressing the need to address both the biases and the potential benefits of these technologies in what she calls “very interesting times.” Her efforts to integrate AI tools within other institutional and academic settings faced significant challenges. Institutional implementation, she notes, requires providing free user accounts, access to necessary systems, and adequate hardware – an investment that, while not prohibitively expensive, is still essential. The initiative ultimately proved unsustainable, and she withdrew from it after two years, describing the process as extremely challenging. This experience reinforced her perception of the broader challenges in integrating AI into institutional and governmental frameworks, where it is likely even more complex. Meanwhile, the art market's reported decline over the past years is leading to gallery closures and is impacting the broader ecosystem of artists, frame-makers, printers, and transporters. Confronted with doubled art transportation costs, Larcher contemplates strategies like on-site production to minimize logistics, which reminds her of her student days: “It is like when I was a student, everything was the same, when I was exhibiting somewhere else, it had to fit in my suitcase and then suddenly I had the art transport and now I have to go back again, it’s like oh, I will be fine, I’ve been there!”

References

Bregman, R. (2020). Humankind: A hopeful history. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Fischer, E., & Larcher, C. (2025, March 15). Feminine beats masculine Energy [Song]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hb2Dt68xuE

Hare, B., & Woods, V. (2020). Survival of the friendliest: Understanding our origins and rediscovering our common humanity. Random House.

Larcher, C. (2024). Dada_Group_1921 [Image]. In AI and the art of historical reinterpretation – Filling gender bias gaps. Prix Ars Electronica. Retrieved August 13, 2025, from https://calls.ars.electronica.art/2024/prix/winners/14174/

Larcher, C. (2022–2024). AI and the art of historical reinterpretation. Claudia Larcher. https://www.claudialarcher.com/work/theartofhistoricalreinterpretation

Sinders, C. (2020). Feminist Data Set [Handbook]. Clinic for Open Source Arts (COSA), University of Denver. https://carolinesinders.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Feminist-Data-Set-Final-Draft-2020-0517.pdf

Working together with

.png)